SACHIYO ITO’S MEMOIR: CHAPTER 16

In Chapter 16, the continuation of her Salon Series exploration, Sachiyo Ito takes us deeper into the cultural heart of Japan through her collaborative programs. Photo of Sachiyo Ito in kimono by Larry Thompson.

Since January 2024 renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

Salon Series: Vertical and Horizontal Threads II

Cultural Introduction beyond Dance in the Salon Series

1. Literature: Poetry

While exploring different aspects of Japanese culture beyond dance, I decided to delve into the literary arts. As I am not an expert in literature, my intention was to rely on the expertise of writers and scholars. Other literary forms, such as essays and novels, felt too vast for me to connect meaningfully to dance—except when they served as the basis for dance dramas. As a result, I often turned to poetry, which has always felt more evocative and approachable as a source of inspiration for choreography.

My first attempt was a historical introduction to Japanese poetry, spanning from medieval to modern works—more specifically, from waka and haiku to Gendai-shi (modern Japanese poetry). Guest lecturers provided context and analysis while I presented classical dances inspired by waka, such as Shigure Saigyo, a Kabuki dance based on the monk and poet Saigyo. I even ventured into Western contemporary poetry—not as a formal introduction, but as a creative wellspring for choreography that explored universal themes. It was a joy to choreograph pieces inspired by poets like Rainer Maria Rilke and Mary Oliver. One special highlight was the opportunity to restage one of my favorite works, Chieko, based on Chieko-shō, which I had first presented at the Japan House in 1980. I was fortunate to collaborate with the beautiful voices of Mary Myers and Beth Griffith in that performance.

Among the most frequently presented poetry programs in the Salon Series were renku (linking verses) and dance, that is, alternating dance and haiku stanzas in linking form in the manner of renku. This idea first emerged through a collaboration with the Haiku Society of America, presented by Japan Society in 2006. (See Memoir Chapter 11: Poetry and Dance.) While most choreographic works in the Salon Series were improvised within a structured framework, the Renku and Dance performances featured “pure improvisation,” involving haiku poets, musicians, and myself in spontaneous creation. When asked by audience members how I managed to combine these art forms, my answer was simple: “The only way it was possible was because the poets and musicians were superb artists.”

Inspired by the success of Renku and Dance, I began offering free workshops at senior centers in Manhattan under the title Dance and Poetry of Japan Workshop. Over the past ten years, I have held six programs, and the senior participants have consistently been enthusiastic and creative. On the other end of the age spectrum, I also led Children’s Haiku and Dance workshops at elementary and high schools. I was deeply moved by the children’s haiku—not only were they beautiful, but they also revealed profound wisdom. These experiences taught me that observing the world with innocent eyes can lead to life’s most meaningful discoveries.

Renku and Performance

Because a core rule in renku is to avoid simply replicating the previous verse, I strove to create a progression—from waterfall to drinking water, to drinking sake, and finally to becoming drunk—in the video linked above. As is customary in Renku-related programs, we invited haiku submissions from the audience at the end. I then improvised dances inspired by those haiku, which delighted both the audience and the participating artists.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series No. 32 Renku and Dance: An Afternoon of Improvisation

2. Literature: From Classic Works

The Heike Monogatari

Inspired by Hoichi the Earless, a tale retold by Lafcadio Hearn (Koizumi Yakumo), I created a dance titled Sound of Emptiness for the 10th anniversary concert of the Salon Series. This work later evolved into a larger-scale production for the 30th anniversary concert of Sachiyo Ito and Company in 2011, featuring singers and dancers portraying the ghosts of the Heike court ladies. Although we didn’t have access to a hanamichi (Kabuki theater’s walkway), we were fortunate to use the audience aisles—from the upper to the lower levels—for the entrance of singers and ghostly figures. This use of space made the transition from the other world feel especially effective.

However, my aim was not simply to depict ghosts. I centered the piece around the teaching of Prajnaparamita—a profound Buddhist sutra—making the work appropriate for the concert’s theme: “Praying for the Deceased of the Great Tohoku Earthquake.” We concluded the performance with a prayer for peace, joined by all company members, musicians, and Rev. T.K. Nakagaki, who inscribed sutra prayers onto lanterns on stage.

Looking back, the collective efforts of artists—both in Japan and abroad—to raise funds and support the victims of the earthquake became a powerful motivation for our performances in the following years. Now, with so many disasters and calamities occurring, it feels increasingly difficult to label them as merely “natural”—they are, in many ways, caused by humans, a result of climate change.

Postcard for the 10th anniversary of Salon Series

Flyer for Sachiyo Ito and Company’s 30th anniversary concert

Gion Shoja

For the 15th anniversary concert of the Salon Series, I choreographed Gion Shoja, inspired by the iconic opening lines of The Heike Monogatari (The Tale of the Heike), which epitomize the teaching of Buddhism, impermanence—one of the core aesthetics of Japanese culture.

The guest artist Yoshi Amao and I embodied the spirits of warriors from the Genpei War (1180–1185), a fierce conflict between the Taira and Minamoto clans that shook Japan during the late Heian period. Though the war lasted only five years, its influence on literature, music, and dance has been immeasurable.

“The sound of the bell of the Gion Temple echoes the impermanence of all things. The pale hue of the flowers of the teak-tree shows the truth that they who prosper must fall. The proud ones do not last long but vanish like a spring-night’s dream. And the mighty ones too will perish in the end, like dust before the wind.”

Despite the gravity of the theme, choreographing a dance defeating a samurai was fun!

Sachiyo Ito with Yoshi Amao. Photo: Larry Thompson

Sachiyo Ito with Yoshi Amao. Photo: Larry Thompson

Flyers for 15th anniverary (Photo: Larry Thompson) and Salon Series 66

The collaboration with Mr. Amao on Gion Shoja was so satisfying, and for Salon Series No. 66: An Ode to Autumn, the theme of impermanence seemed especially resonant during the autumn season, I invited him to the program to present the dance once again. I felt the dance would be suitable for autumn, the time when fallen leaves evoke deep reflection on the transience of life.

YouTube Clip: Gion Shoja from 15th Year Anniversary of Salon Series

3. Ma: The Japanese Cultural Concept

Ma in Space

We cannot speak of Japanese performing arts or Japanese culture without mentioning Ma, so I have presented several programs in the Salon Series inspired by Ma.

What is Ma? Ma is the Japanese concept of space and time. It refers to the interval between spaces, and the pause between moments. And yet it is not an empty void; it is a space filled with meaning.

Before I encountered Ma as a distinctly Japanese concept through the writings of Edward Hall*, I had only a vague sense of it—more as something personal, something learned through dance training: a felt sense of space within timing. The following reflections I offer are only my perspective as a dancer, for I am not a cultural anthropologist.

My exploration of Ma in the Salon Series began with the idea of approaching it as it exists in both space and time. I asked myself: Can we create a moment outside our ordinary perception of time and space? A serene experience where everything pauses—where time and space seem to freeze, and we exist fully within that stillness.

In Salon Series No. 48 Ma: Creating Sacred Space and Time Here and Now, my intention was to evoke a sense of sacredness in the physical space where we gathered, and in the musical space created through the sparseness of the Buddhist chant Shomyo and the sound of fue (bamboo flute). To deepen this sacred atmosphere further, I incorporated Shakyo, the meditative practice of copying Buddhist sutras into the costumes. The calligraphy featured the Shiku Seigan (The Four Great Vows, such as the vow to save all sentient beings), which I had sewn onto the kimono sleeves on stage as a visual and spiritual element.

Color played a symbolic role: black costumes accented with red, with layers of white revealed later in the performance. In the opening scene, the use of kurogo (stage assistants in Kabuki) in black near my dancers and myself seemed highly effective.

One unexpected challenge arose: The calligraphy ink was too wet to attach directly as sleeves to the costumes. It reminded me that “having an idea in the head doesn’t always work in practice!” Fortunately, my stage assistants clad in white kimono, Mariko Suzuki and Monika Hadioetomo, who were both costume designers. saved the moment by carefully drying the ink with paper towels on stage. They executed the task with grace and in a meditative manner. When the ink was dry and ready, they sewed both sleeves to the white kimono while I was wearing it on stage.

To conclude, we invited the audience to join in a walking meditation as a shared closure to the experience.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series No. 48 Ma: Creating Sacred Space and Time, Here and Now

Flyer for Salon Series 48. Photos by Larry Thompson and Akiko Nishimura

Ma: Sacred Space II was presented as nature worship in Salon Series No.55 Creating Sacred Space II: Japanese Nature Worship and Labyrinth Walk. This time, I incorporated Shinto ceremonial elements of reverence for nature, such as water purification ritual into the performance space. I believe we were able to transform the venue, Tenri Gallery, into a sacred space without relying on theatrical effects, despite its intimate size, which is typically too small for a labyrinth.

For the music and singing, I selected Etenraku Imayo from gagaku, Japanese court music. The goddess and her attendants descended from the gallery’s upper balcony as they sang, signifying their divine arrival from heaven. Bells echoed through the space to ward off evil spirits during our dances—performed by the goddess, her attendants, and myself.

To evoke a labyrinth, I shaped a winding path with rope, connecting the performance area to the corridor and entrance. Each audience member held a candle as they joined in the walking meditation. At the closing, we gathered in a perfect circle, an expression of unity for peace.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series No. 55 – Creating Sacred Space II: Japanese Nature Worship and Labyrinth Walk

The Labyrinth of Salon Series 48

Ma in Time and Iki

Ma in timing is one of the most vital elements in the performing arts, whether in dance, music, or drama. Its significance also extends to our social interactions, shaping conversation, emotional expression, and energetic presence.

In dance, Ma can be structured by musical rhythm (hyoshi) or guided by breath. Yet in Japanese, breath is expressed in two distinct ways, though both are translated into English simply as “breath.” The first is kokyu, referring to the physical act of inhaling and exhaling. The second is iki, which encompasses not just the physical function, but also intention and the internal energy known as ki or chi.

A powerful example of iki is found in the traditional orchestras of Kabuki and Bunraku. These ensembles perform without a conductor, yet the musicians begin, pause, and resume in perfect unity through shared breath. It’s an intuitive synchrony, cultivated through practice and passed down through generations.

Kabuki critic Tamotsu Kaoru once stated, “Iki is the foundation of acting.”

My personal journey with breath began in the 1980s when I first encountered yoga. At the time, I struggled with deep inhalations and exhalations. I later realized this difficulty may have stemmed from my dance training, which emphasizes concealing breath—even during high-impact movements. Dancers and actors must appear effortless on stage; therefore, shallow, controlled breath becomes essential. Here, breath transforms into iki—an intentional, internal force.

Curiosity led me to explore breath’s role in healing arts, which then inspired Salon Series No. 49: Ma in Healing Arts and Dance. My guest was Wataru Ohashi, the founder of Ohashiatsu (the Ohashi Method). His charismatic presence drew many audience members into participating. Pairing strangers who sat next to each other to try shiatsu techniques brought laughter and connection, while exploring iki through shared breath proved deeply engaging.

I also demonstrated how iki is used to convey emotion in Okinawan female-style dance. In portraying sadness, subtle breath supports the graceful flow of movement, but it must remain hidden from view, felt rather than seen.

Iki (breath with control) and kokyu (breath as physical function) form an expansive topic across the performing arts. For the Salon Series, I could only touch on the related practices in two programs that featured Karate and Okinawan male-style dance, the dance form influenced by Karate, in Salon Series No.12 and Salon Series No. 29. These presentations revealed how critical it is to grasp hara.

In all the traditional martial arts and traditional music, including utai singing, breath originates from the abdomen, known as hara. It is the body’s energetic center, grounding one's stance and channeling power through movement. Hara is the anchor, and mastering it is essential in dance, Okinawan dance, Japanese dance, martial arts, and in healing arts such as Mr. Ohashi’s.

While unrelated to the topic, I wish to express heartfelt gratitude for the kindness and long-standing friendship of Mr. Ohashi and Mrs. Ohashi, who generously hosted a celebration at their Manhattan home in 1988 when I received my Ph.D.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series No. 49 – Ma and Breathing in Dance and Healing

Flyer for Salon Series 49. Photo by Mariko Suzuki

Ma in Dance

So now how can we achieve Ma and iki successfully in dance?

Ma is an essential part of dance learning and yet cannot be learned. Well then, a student may say, “Not fair!” Ma is crucial, and yet elusive. Still, finding the right Ma is a journey every dancer and artist must pursue.

The same was expressed by the noted Kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjuro VII, “There is Ma you can be taught, while there is Ma you cannot be taught.”

According to another great Kabuki actor, Onoe Kikugoro VI, “Ma is 悪魔の魔 (Ma of devil), 魔術の魔 (Ma of magic).” That means if Ma is executed poorly, it will destroy the acting, dancing, even the whole play, while if implemented well, it can be magic to mesmerize the audience. I must say, “fearful and awesome!”

The Kanji character he used in his analogy was different since Ma is written as 間, but it cleverly mentions how, on the one hand, it is difficult to use it properly, while on the other hand it can be used to great effect in art.

Then how can we make 間 magical as 魔? The answer lies in refining one’s craft.

If you’re not a dancer, feel free to skip the next section, for it summarizes my dance instruction.

We first go by the prescribed timing of music, the rhythm (hyoshi), which is clearly punctuated by the music. A difficulty may be that there is more than simply following hyoshi in mastering a dance piece. It is characteristic of Japanese music to place importance on melody more than rhythm. Furthermore, classical choreography often requires movements with the words—such as at beginning or the end of a word or phrase. The latter poses an additional difficulty for non-Japanese-speaking students, one they can however overcome through their studiousness.

Then, we brush up our Ma through breath—more precisely, breath control—with iki: long and short breath, deep and shallow breath in executing movements and gestures. They are first controlled by intention: how you want to express the emotions or the meaning of the lyrics, the character in dance. Then find a good Ma in between the clear musical stomps: Try going against the music rather than going together with the tempo of the music or simply pause. Yes, the pause. Ma is the essence. It is not a static pause in dance. As is said in Noh, dance and acting are stillness in silence. Energy flows through after the punctuation of words and the rhythmical cues.

The above is my general instruction in lessons, but over the years I began to think of another word to be used, or should I say a linguistic approach to reflect what I really mean. It is “resonance,” as I believe dance can have an effect of resonance as in music.

The word suggests audiences create their universe as they hear the echo in their mind.

Does it sound hard? Not really, experimenting is a fun process. There, you are given freedom for your own creativity, although we get the criticism that there is no freedom in traditional dance. I need to remind those who consider traditional art as rigid: Japanese culture is a culture of pattern, going into pattern and out of it. Once you master discipline, the basic, there is freedom. So have fun!

Then, as a part of investigation of Ma, I presented Salon Series No. 54: Resonance in Music, Dance, and Literature. My guest speaker and shakuhachi player was James Nyoraku Schlefer, to whose music I danced. He demonstrated the importance of sound—to be absorbed in the sound, which gives us meditative quality—more than melody or rhythm. Also, realizing the importance of pause/silence in haiku, I invited John Stevenson, the haiku laureate. (Refer to Chapter 11 of this memoir for his insightful comments.)

My aim in the program was to show how important it is to have resonance, the echo in music, as well as resonance in the movements of dance, and to consider this concept: Dance does not and should not end at the punctuation of or stamp of sound in music. My further quest was, “Can I send an effective message of the dance through the pause, by doing nothing, just as Zeami the Noh dramatist said, ‘Doing nothing is captivating’?”

Here it may be interesting to know that Roh Ogura, the composer and writer, mentioned in his book Japanese Ear that the Japanese ear has a fondness for the silence after a music performance and a temple gong.

Now, I know you are reading this, and we are not facing each other, but what I shared in the Salon may be interesting for you.

““Please close your eyes. Keep breathing easy, in and out, feel space around you, and you are the space itself, and you are expanding.

“Here is the Gong. Keep soft breathing, 10 seconds.

“…

“Open your eyes.

“Smile!””

Did you hear the echo, and even hear the silence after the sound is gone?

Ma is not a void, but alive and critical.

My Shimai (Noh dance) teacher likened the stillness, the non-movements, to pressing both brake and accelerator pedals in driving at once: The action holds both forward and backward tension. When that control is released, energy radiates outwards. But please, don’t try that in your car. We’re speaking about dance.

Resonance after motion. Silence after sound. What message can we send in the space, the “Ma,” that follows?

In conversation, silence between words can be powerful: “Will you marry me?” “……”

In literature, The Pillow Book exemplifies simplicity and resonance: “Spring, dawn.”

The two words, that resonate afterward, offer us infinite meaning that we can enjoy.

A haiku by Basho echoes similarly.

An ancient pond—

A frog jumps in

The sound of water

The splash fades, then comes the deeper stillness, inviting us into timelessness.

Things are unsaid but resonate after sound and movements are performed or words are spoken, offering limitless opportunities for audience/reader/viewer to participate in the completion of the art with their imagination. What freedom we have! The unimaginable wonder of Ma: Resonance after a word, movement, or sound offers the audience the freedom to imagine, to co-create the meaning of art with artist.

Ma has been one of my lifelong quests, and yet I am not certain if I could see any of it. But I hope this chapter offers you a window to look into this fascinating subject in the arts, and in our lives.

Cultural Introduction Beyond Dance: Flower and Tea

A decade into the Salon Series, still exploring the crucial yet elusive concept of Ma, I began to broaden my efforts. Ma cannot be taught in the conventional sense, and that may seem unfair to students. Still, finding the right Ma is a journey every dancer and artist must pursue.

Recognizing that its scope goes beyond the performing arts led to the introduction of other cultural forms: Ikebana (traditional Japanese flower arrangement) in Salon Series #56; Chanoyu/Sado (茶道), the Japanese tea ceremony in Salon Series #57. For the Ikebana program, I performed classical dances themed around flowers: Shikunshi (The Four Noble Flowers), Aki no Iro-kusa (Flowers in the Autumn), and Shiki no Hana (Flowers in Four Seasons). For the tea ceremony program, I was fortunate to have Cha Ondo (Tea Ceremony Song) accompanied live to complement the tea ceremony demonstration.

The Ikebana demonstration sparked the idea of creating a dance centered on a flower theme, leading to a collaboration with contemporary florist Katsuya Nishimori in Salon Series #57: Flower Petals Fall, But Not the Flower. The title was inspired by the teaching of Kaneko Daiei, as mentioned in Chapter 4 of this memoir, which details my belief in dance, “flower theory.” This dance unfolded as sequences in the dream of a playful, vain woman, proud of her beauty. In her dream there appears a lavish flower arrangement, built by the florist in real time on stage in Kurogo costume.

Destruction: Consumed with jealousy toward the flowers for their beauty, she destroys the blossoms in a fit of rage.

Regret and Awakening: Overcome with remorse and sorrow for her deed, she glimpses a light of redemption.

Acceptance: Acknowledging the fragility of emotions—like flowers— she prays for the “real flower” that transcends temporality.

The woman walks to drape a white net across the stage over fallen petals on the floor, covering them as if she were consoling these fallen lives into a peaceful sleep. At the end, the scattered petals were meant to symbolize the transient nature of life.

Flyer for Salon Series 57. Flower arrangements by Katusya

Flyer for Salon Series 56. Ikebana by Masako Gibeault

Beyond Barriers

The initial focus of the Salon Series was to foster “understanding beyond boundaries of culture and ethnicity through the introduction and exploration of Japanese arts and culture.”

Over time, however, this evolved into a profound message:

“We are all human beings. Regardless of cultural, racial, or physical differences, let us overcome these boundaries and work together.”

One of the programs that embodied this vision was Salon Series No. 65: On the Human Spirit. It was a multidisciplinary collaboration featuring poetry, dance, music, and sign language.

Inspired by Ishigaki Rin’s poem Taiyo no Fumoto de (At the Foot of the Sun), the program began by portraying the world we live in as a beautiful place, blessed by the sun. The performance began by celebrating the beauty of our world, blessed by sunlight. Through poetry and singing, we expressed wonder and gratitude.

The dance segment that followed represented tragedies of our human history: war and natural disasters such as earthquakes.

In one symbolic gesture, I shredded pieces of the inner sleeves of my kimono to express the torn state of the human spirit. Then, I began tying them together, signifying the act of healing, of picking up the broken emotional and physical pieces of ourselves. The reuniting of the fragments was a metaphor for healing and reclaiming emotional and physical wholeness.

Audience participation was an essential part of this process. I invited them to join me in tying the fragments together into one long string as they sat next to each other in their chairs. This act symbolized unity and the possibility of recovery from both natural disasters and personal tragedies through mutual and collective support.

To close the program, Amelia Hensley (of Deaf West’s Spring Awakening on Broadway) taught sign language to us, dancers, poetry reciters, and audience members. We were so delighted to see the audience engage and try the sign language gestures. The vocalist Beth Griffith then sang “Amazing Grace,” a light to guide us to healing.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series No. 65: On the Human Spirit

Flyer for Salon Series 65

Dance and Prayer

Amid the crisis of COVID-19, I felt a deep need to offer a message of prayer and healing. In response, we live-streamed Salon Series: Prayer for Healing and Peace through the Symbolism of Cranes to welcome the New Year with hope. Drawing on Japanese traditions, the crane—symbolizing health, longevity, and peace—became our central motif.

The program featured classical dances themed around the crane, an origami paper-crane folding session, and my original dance works honoring the lives of those we had lost. It was a gentle offering of peace, renewal, and collective memory.

Also featured in the program was my new piece titled Memories, dedicated to all those who died during the pandemic.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series No. 67 Prayer for Healing and Peace through the Symbolism of Cranes

The dance in the link below is an excerpt from Seiten no Tsuru (Cranes in the Blue Sky). Though it is not from No. 67, but from No. 63, it will give you an idea of the classical dance Seiten no Tsuru.

YouTube Clip: “Crane” from Expressions in Traditional and Contemporary Dance in Salon Series No. 63

The Meaning of Dance

What is most important in dance? For me, it is not technical virtuosity or performance for the sake of display. Dance, at its core, is an offering and a prayer. This intention was at the heart of Salon Series No. 67. I was pleased that our crane dance conveyed this message so clearly. It affirmed the deeper meaning of dance: to connect, to heal, and to transcend.

Closure of Salon Series

As the saying goes, “Where there is a beginning, there is an ending.” The final Salon Series, No. 74, was held in December 2023. My photo appeared in Shukan NY Seikatsu, was captured in a moment of emotional intensity, perhaps even a bit of theatrical distress, and still brings a smile to my face. It was taken after I recreated the earthquake stanza from one of the audience members, after moving with fear, possibly rolling on the floor in response to the earthquake scene.

I have been deeply fortunate to have longtime friends and collaborators John Stevenson, Yukio Tsuji, Beth Griffith, and Masayo Ishigure join me in closing the Salon Series, which spanned a quarter of a century.

Thanks to the unwavering support of audiences and guest artists, I was privileged to embark on this incredible 25-year journey. The Salon Series was not only a platform to share my knowledge as a dancer and educator, but also a source of profound learning. Each presentation led me to explore vast and varied subjects so expansive that they stretch beyond the scope of a single lifetime.

This journey reaffirmed a humbling truth: The more years I spend pursuing my path and craft, the more I realize how little I truly know.

Above all, the artists and audiences have gifted me with deeper insight into our shared human nature. No words can fully express my gratitude.

With deep bow

From Shukan NY Seikatsu

Salon Series No. 65 Review

The Salon #65 performance ended ecstatically with vocalist Beth Griffith singing Jacques Brel’s If We Only Have Love. With the full cast onstage, Ito’s parting words to the audience were to observe nature and engage the love that connects everything on earth.

— Dalienne Majors

60th Salon Series Welcomes Shogo Fujima

Ito performed “Petals Fall But Not the Flowers” and “Only Breath” with Indian and European dancers, closing the event in a spectacular atmosphere.

— Kaoru Komimi

Shukan NY Seikatsu, June 24, 2017

Flyer for the 60th Salon Series installment. Photo by Jason Gardner.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!

Sachiyo Ito’s Memoir: Chapter 15

Sachiyo Ito’s Memoir: Chapter 15. Photo by Jefferson Maia

Since January 2024 renowned dancer, dance educator, and choreographer Sachiyo Ito has been serializing her memoir on JapanCulture•NYC with monthly installments, each chapter revealing a different aspect of her early life in Tokyo and career in New York City.

Ito offers of a profound exploration of the experience of dedicating herself to traditional Japanese dance at an early age, arriving in New York City during the tumultuous ‘70s, and making a successful career in the arts. Each chapter offers a glimpse into the complexities that shaped her journey. It is a literary examination of not only Ito Sensei’s life, but of how New York City’s culture evolved over the decades and what sacrifices one must make to achieve a thriving career in the arts.

The memoir is an invitation to delve into the layers of a creative life and career that has spanned more than 50 years. As a work in progress, it is also an invitation for you to offer your feedback. Your insights will contribute to the evolution of this extraordinary work.

To read all the chapters, please click here. For more information about Sachiyo Ito, please visit her website, dancejapan.com.

Salon Series: Vertical and Horizontal Threads

(Vertical Threads connecting various cultures and peoples around the globe and Horizontal threads from the ancient to modern, the classical to contemporary 縦横の糸:横は世界を巡り、縦は古典から現代)

Held three times a year, the Salon Series was a series of grassroots programs presented in various formats and subjects, informing and investigating aspects of Japanese cultural and artistic heritage. The dialogues between the world class guest artists and the audience often led to new insights and deeper understanding, not only of Japanese culture and art, particularly dance, but also human nature.

By the time of its conclusion in 2023, the Salon Series had presented 74 programs to the public, and three additional special anniversary concerts. The series lasted for 25 years, far longer than I had expected at the onset. This continuation was made possible not only by my passion to introduce Japanese art and culture to the world outside of Japan, but also by the support of the audiences and guest artists.

There have been many wonderful collaborators of such incredible artistry and kindness who have joined me at Salon Series. I have no words other than those of deep gratitude for their willingness to collaborate with me, the minor artist.

One of the aims of the Salon Series was to introduce Japanese art and dance forms in depth. In addition to dance and music performances, demonstrations, lectures, audience participation, and Q&A sessions with the guest artists were important components of the programming. Audience members both familiar and unfamiliar with Japanese arts and culture had many questions. However, those who were familiar with the topics would ask questions that led to lively discussions, insightful perspectives, and new discoveries.

When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Lemonade: The Story Behind the Salon Series

The inspiration for the Salon Series was not my mission to introduce the Japanese arts to the wider world, which I have pursued all my life, but a bad review that I received from a Japanese critic for a concert I had given. The most upsetting aspect of the review was the critic’s ignorance of traditional Japanese theater and its practices, such as the Kurogo (stage assistant) being seen and handling props, and not using the curtain to delineate scenes, as a western production would. These are conventions I follow when presenting centuries-old Kabuki dances.

Once I began performing outside of Japan, my audiences were mainly non-Japanese, and I developed a format of demonstrations and lectures for American schools, libraries, and museums, with the intention to relay how the original productions should be since they would have little knowledge of conventions and traditions.

However, the writer was a Japanese and a professional dance and theater critic who should have been well familiar with these conventions. Then I thought: Why not begin a program for both Japanese and non-Japanese? It could be a presentation about our arts that goes beyond superficial information and explores Japanese arts in greater depth. Furthermore, discussions with featured artists would provide a valuable forum for the exchange of ideas. I hoped that this might serve both as enlightenment and entertainment. Little did I know that this tiny seed of an idea would grow to have a huge impact on my life, leading me to collaborate with great artists, scholars, and experts from all over the world—an incredible and fortunate privilege.

How It Began: A Gallery in SoHo

Having an idea does not bring a project to fruition. I went around to several cultural institutions with my proposal but was greeted only with rejection. Only one place, a small gallery in SoHo, showed any interest in the venture. One day I found myself on the street outside of Tenri Cultural Institute, uncertain if I was in the right place or not. “Plucking up my courage,” to use the English idiom, I knocked on the door and was graciously welcomed inside by Rev. Toshihiko Okui, the institute’s director. I presented my plans and waited while he considered them. Finally, he said, “Well then, let’s begin and see.” Thus, my proposal was accepted. No words can express how grateful I am to Rev. Okui, for at the time, I was nothing but an unknown dancer and a stranger to him. He would later connect me to the Tenri Gagaku Society of New York, which became one of the few guest artists I would invite to the program repeatedly, another thing for which I owe him a debt of gratitude. Not long after our initial meeting, Tenri moved to its current location on 13th Street, and I presented the Salon Series there for more than twenty years.

Salon Series No. 34 featured the second collaboration with the Tenri Gagaku Society of New York. I wanted to introduce the ancient Japanese songs, a part of the Gagaku repertory, since we had introduced repertory imported to Japan from parts of China and other places in Asia in the earlier Salon program. For this occasion, I created a trio dance called Kashin. I chose the song Kashin for this new work because I was very intrigued by how it resonated with a song from Sui Dynasty in 7th century China. The song says, “Let’s celebrate this happy occasion! May this joy be limitless, last ten thousand years, and grow forever!”

The fact of the matter is that it was not easy to follow the words of the song. My dancers, and even I, from time to time, got lost as to where we were in the music while rehearsing. This was because of a prolonged vowel sound which lasted several minutes. During the program, I showed the Kanji characters to the audience on a large piece of paper, while I had one of the singers pronounce each word. The slowness of the progression of music made me realize that there is a difference between the body clocks of ancient and modern times. For the Japanese of the Edo Era, time was kept at a slow pace, marked only by temple gongs that were struck once every two hours.

The modern world has become far more aware of time and counts exactly not only hours but minutes and seconds. Japan, in particular, has become known for its punctuality.

This reminds me of a story from my high school days. I had a date at Shibuya Station, the closest station to my school. My date was late. As I waited, I grew more and more anxious, getting worried about his well-being, wondering if an accident was the cause of the delay. An hour later he arrived, telling me that he had wanted to test me to see if I would wait for him. I never saw him again. I doubt anyone would wait longer than half an hour for someone nowadays.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series #34: Gagaku and Ancient Song of Japan

Comparison with Various Dance Cultures

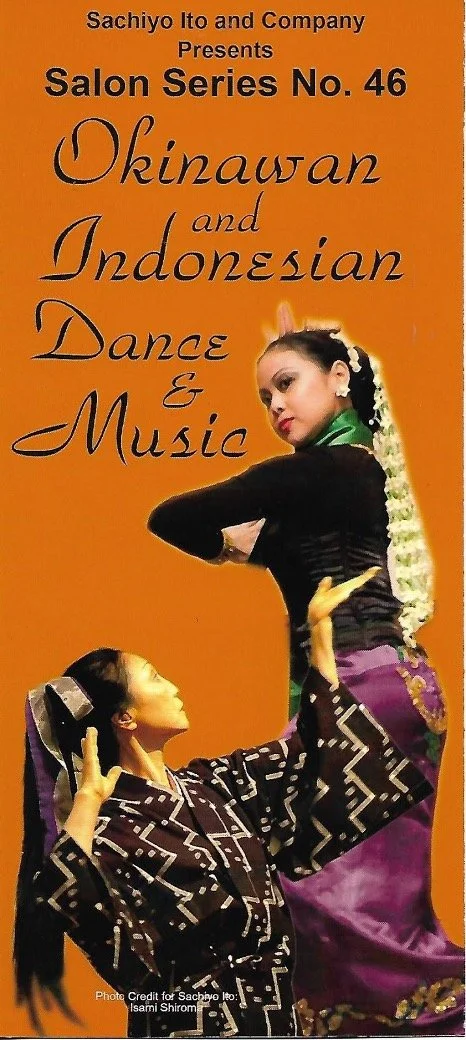

From the very inception of the Salon Series, I have been eager to present comparative studies of dances in Asia. The countries I included in the Salon Series were Okinawa, China, India, Korea, Tibet, and Indonesia. We held programs featuring Indonesian and Okinawan dance on more than one occasion.

Okinawa is the southernmost tip of Japan, and due to its geographical location, unique history, and diversity in the arts, it is one of the most interesting regions to explore among southeast Asian countries.

My fascination with Okinawa began when I first visited the islands in 1976. In the 1970s, I began researching the roots of Japanese dance, and in Okinawa I discovered beauty and traditions that the mainland may have lost over time. Eventually, my interest led to my doctoral dissertation, The Origins of Okinawan Dance, which I discussed in Chapter 8.

Because of interest shown by artists and audiences in the similarities and differences between Japanese mainland and Okinawan culture, I presented many programs with Okinawan themes, often comparing music and dance. One of the themes of these programs was Karate and Okinawan dance. I was pleasantly surprised and happy when the first Karate program attracted a large audience, more than a full house, so I added two more Karate and Okinawan dance programs with different focuses and different Karate masters. And yet, Okinawan Court Opera: National Identity of Okinawa, a program about Tamagusuku Chokun, the 18th century dance master and creator of Kumi Odori (Okinawan Court Opera) did not attract a crowd. Perhaps I was the one who enjoyed it more than the audience, because I was passionate about voicing how important the arts are to cultural identity, not only for Okinawa, but for every country.

In addition to traditional Okinawan dances, I was also keen to introduce contemporary Okinawan dances, among them Nanyo Hamachidori (Plovers in the Southern Pacific) the most interesting piece that I presented several times at the Salon Series and other concerts. Fortunately, two decades before I began Salon Series, I was given permission to perform this dance by my teacher Takako Sato, who had restaged it as a solo for her group’s concert at Asia Society in 1986.

Getting sponsorship from Asia Society and the Okinawa American Association of NY for this performance was not an easy task, but I was so grateful to them for their support, for I believed that New York audiences should discover and see the beauty and artistry of Okinawan dance.

Hamachidori (Plovers on the Beach) was choreographed by Tamagusuku Seiju in the late 19th century. It featured a particular hand gesture derived from court dance technique: the repetitive, soft undulation called koneri-te (kneading hands). It was Iraha Inkichi who adapted it to create Nanyo Hamachidori around 1930. Along with koneri-te, he incorporated elements of ballet in the dance after his tour in Hawaii. These hand gestures and movements are intriguing to anyone who watches Okinawan dance. As a continuation of the investigation of hand gestures, I invited guest artists from Indonesia to two different programs.

*Ms. Sato’s performance was the second time an Okinawan dance troupe visited New York, Miyagi Minoru’s troupe being the first in 1981.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series # 62: Traditional Japanese Dance and Theater in Contemporary Performing Arts

In one of the Indonesian collaborations, Salon Series No. 10 with Dr. Deena Burton, we discussed female power in performing arts in each country. During a time when dominance of women by men was the norm in all parts of society, there was yet a strong feminist voice in the theater. In the millennium, women’s power and equality became a commonplace idea, but Deena and I talking about female power in each other’s traditional dances in the early 1990s was a unique subject.

Influence and Comparison of Japanese Classical Theater Forms with Contemporary Theatre and Dance Forms

The historical progression and evolution of art forms has always been my great interest, and I wanted to compare the traditions I was familiar with to contemporary dance, such as Butoh and ballet, and contemporary theater.

In Salon Series No.62: Traditional Japanese Dance and Theater in Contemporary Performing Arts, my guest speaker and artist were Yoko Shioya from Japan Society and Annie B-Person, the director of Big Dance Theater, the avant-garde theater group to whom I taught Okinawan dance. Along with their presentations I demonstrated the basics of the three classical theater forms: Noh, Kabuki, and Okinawan court dance. We attracted a large audience, for we aimed at illustrating the influences of those dance styles on contemporary theaters in the 21st century, a topic intriguing to both theater goers and dance enthusiasts. It was a huge task for me to demonstrate three classical theater and dance forms in a limited time, for I had to summarize the forms, and generalization is always dangerous and can lead to misunderstanding.

One aspect of the demonstration was to show the differences in facial expression between Kabuki and Okinawan dance. In Okinawan court dance, one is not supposed to show obvious facial expressions, just as if wearing mask in Noh. In Kabuki dance we do use facial expressions, although they are quite subtle. I must admit it was hard for me because of my decades of training since childhood.

Simplicity and subtlety are two of the major characteristics of Japanese culture. Restrained, almost hidden, feelings are the core of expression. In Noh, to suggest hidden reality underneath the surface reality is the ideal, and Noh masks serve this purpose well. Such control seems to attract practitioners of modern art and modern performing art. The audience is made to search for the true expression in the distilled, carefully chosen motions, where we find freedom of interpretation. I wonder if that freedom of choice is what modernism prefers. Or is it attracting a certain kind of audience?

Perhaps that was what William Butler Yeates was trying to achieve when he showed his Noh plays. He did not care about attracting the masses, but only those who might understand his literature, poetry, and themes.

In this Salon, I also presented my experimental dance, Umie (To the Sea), a fusion of Japanese dance and Okinawan dance. As the costuming difference is important for us to understand the dance forms, I had the costume designed to combine Okinawan and regular Japanese kimono styles. In the dance, I incorporated Koneri-te, but I took liberty to add folk elements, along with faster execution of hand movements inspired by the tempo of the music. I must say that the program was full of agendas.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series #62 – Traditional Japanese Dance and Theater in Contemporary Performing Arts

In Expressions in Traditional and Contemporary Japanese Dance in #63, we explored the contemporary expressions in Japanese dance and ballet with Shoko Tamai on the theme of Sky, Water, and Fire. Live music was provided by Yukio Tsuji, the composer and percussionist, with whom I have collaborated since the mid-1970s, as well as by Beth Grifith, a singer and vocalist.

Collaboration with Guest Artists

Over the years, I showed not only the differences and similarities of our Japanese traditional forms with guest artists, but I also enjoyed creative collaborations with many gifted artists from different cultures.

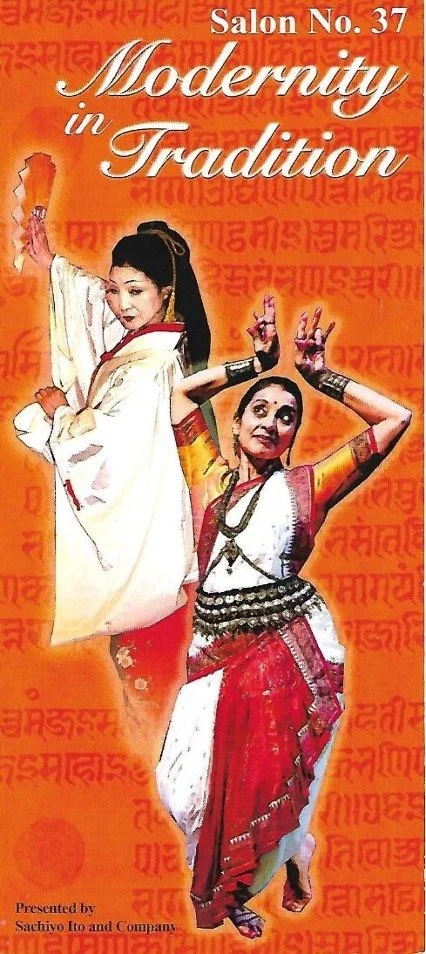

The collaboration with Rajika Puri, an Indian dancer, was an honor for me. As you can imagine, my guest artists had very busy schedules, so I was pleased that we could work out the performance with only two rehearsals. That program, Salon Series No. 37, was accompanied by traditional flutes of India and Japan, played by Ralph Samuelson and Steve Gorn. We reversed the musical accompaniment of each country and danced to it, and the switch was enjoyed by both the audience and performers. One of the most pleasing comments from the audience was, “I was blown away by how similar Indian dance and Japanese dance are!” Well, actually, we paralleled our gestures and movements as they emerged and inspired the other’s.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series #37: Modernity in Tradition (1:54)

My comparative studies extended beyond Asia to include Spain and Russia.

My longtime dream to work with Flamenco guitar came true in Salon Series No. 51: Expressions of Love in Japanese Dance and Spanish Dance. I loved dancing with Juana Cala and to the Flamenco guitar played by Jose Moreno. For our creation, we exchanged standard instruments: Her dance was accompanied by Shamisen, while mine was accompanied by Flamenco guitar. Each of us danced expressing love in our own tradition, but united happily at the end.

Nodding to the musicians as I turned back, the signal for the musicians to move on to the last phrase of music and the dancers’ final steps and pause was such a fun moment.

There was one thing I was quite worried about in presenting this program, though: the floor. Juana had great stomping power, and I feared that the gallery floor might be damaged. I was so worried about this that I increased my insurance premium. However, there was no damage after our performance, not even the slightest scuff. To say I was very relieved would be an understatement.

YouTube Clip: Salon Series #51: Expression of Love in Japanese Dance and Spanish Dance

Walking

Recently, a friend’s family named their newborn son Ayumu. I thought, “What a wonderful name it is!” The word used for the boy’s name is the Japanese verb which means to walk, the same verb as aruku. I could infer what the family wished for him: to grow up in good health, progressing little by little onward and forward.

In Salon Series No. 44: The Art of Walking, we explored walking, the very fundament of dance, as used in three different styles: ballet, modern dance, and Japanese dance. We discussed how and why we walk the way we do in each style and how this is influenced by cultural and social factors. I demonstrated how to maintain the body’s center of gravity low and downward, to achieve the characteristic gliding walk in Japanese dance. I then discussed the reasons for these characteristics, which are known to dance and theater scholars and ethnomusicologists in Japan but not to wider general audiences. Fascinating subjects and favorites of mine, about which I often talk during my demonstration programs at schools and cultural institutions are the etymology of the words for dance—“mai,” “odori,” and “buyo”—the insularity of the country, its geography, and even its architecture and agriculture. But for now, let me put these subjects for another chapter of my memoir.

As we all know, walking is the simplest, most basic movement in dance. In addition to being the physical foundation, it is also of great significance in delivering the message of the dance. It is such a simple movement, and yet, it is the hardest, which I find true in any art form and anything we do in our lives. In Japanese dance, there is a saying: “After ten years, you start to walk properly.” Even at my age, after seventy years of dancing, I am still learning it. It is an art form, just as Gunji Masakatsu, the prolific writer and one of the greatest scholars on Japanese performing arts, pointed out. He called it Aruku-gei (the Art of Walking). In the dances Gion Shoja and Resonance, even though I was the one who choreographed them, the most difficult part was walking off stage at the end, but I had to incorporate the exit walk into the choreography since it was essential in conveying the themes of those dances.

Dance has always been a metaphor for life for me. A dance can express our life events, our human emotions. Often it mirrors where we are in the stage of our life. In dance, we can show our life in a short time like a snapshot, condensing it or taking a single fragment. Walking in dance can serve that purpose well as a distilled movement, showing the essence of dance and its message. In doing so, we also hope that the expression or message is not simply personal, but universal, showing emotions that we all share.

In our day-to-day life outside dance, our walk can also show how we are feeling, heavy on one day, light on another, and it exhibits how we hold our emotions both inwardly and outwardly as we trod on the path of our life.

Quite often, thinking about the miracle of walking leads me to think about the miracle of life. To take a single step requires nerves, muscles, blood, and brain to function together almost miraculously! What a feat of coordination it is. Many speak of the miracle of Jesus walking on water, but I must say that even walking on the earth is a miracle. I used to observe my dog as he walked, following behind him, bending low to get a better view. I know it sounds funny, if you picture how I was following him, but the coordination of his four limbs is incredible.

I have had a fracture in my foot and knee injuries that required surgeries. When such injuries and operations make us temporarily unable to walk, we realize how blessed we are to have the ability in the first place. Such experiences, along with passing by people on crutches or in wheelchairs, remind me of how precious the gift of walking is. Venerable Thich Nhat Hanh taught, “Walk on the earth as if you love the earth, since when you walk in anger, you spread anger.” His teaching shows us that love is so important to nature, both sentient and insentient objects, to others, and to oneself.

In the upcoming Chapter 16, I will talk about the Salon Series from a different perspective than in this chapter.

To read about two guest artists who stood out, Robert Lala and John Stevenson, please refer to Chapter 6 and Chapter 11, respectively.

The posting of this chapter to JapanCulture-NYC.com was paid for by Sachiyo Ito and reprinted here with her permission. Susan Miyagi McCormac of JapanCultureNYC, LLC edited this chapter for grammatical purposes only and did not write or fact-check any information. For more information about Sachiyo Ito and Company, please visit dancejapan.com. ©Sachiyo Ito. All rights reserved.

Support JapanCulture•NYC by becoming a member! For $5 a month, you’ll help maintain the high quality of our site while we continue to showcase and promote the activities of our vibrant community. Please click here to begin your membership today!